My Sister and I Didn’t Speak for Decades. Could a Baby Change That?

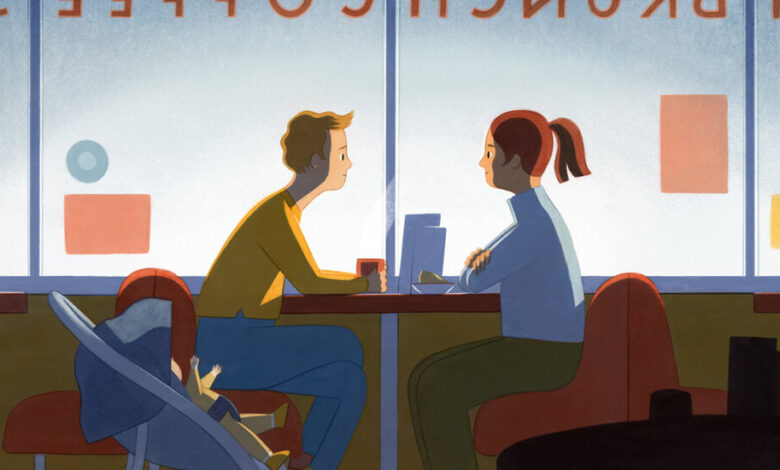

The woman in the vegan diner mentioned her thumbs. They looked like they had been hammered flat, just like mine. I felt the rush of connection, followed by the ache of regret. This woman, my sister, was a stranger.

We had last seen each other more than 30 years ago. I was 7; she was 29. We were burying our father.

Over those many years apart, I often wondered why she had disappeared. Was a little sister so dispensable? My grief and resentment had calcified into something internal and essential, like bone. The prospect of reconciliation, which had once buoyed me, was long gone. Yet here she was, in Chicago to meet my newborn.

Alcoholism had ravaged our extended family, sparing no one. Even those who were not addicted suffered its caprice. She married an alcoholic. I became one. But, without knowing it, we began parallel journeys of recovery in 12-step meetings. She found a lens to understand the erratic behavior of relatives who were sparkly but sometimes cruel. I began to see myself and my own imperfections more clearly, and realized I didn’t need an apology to forgive her.

The disease drove us apart, but perhaps, with the birth of my first child, recovery could bring us back together. In our family, there was a history of long-held grudges among siblings. It felt like an inheritance that I didn’t want to endow my daughter.

My sister and I hailed from a colorful but complicated clan full of people both witty and sharp-tongued. Our grandmother, a newspaper columnist, was a notorious drunk among the country-club set of small-town Maryland. Three of her four children suffered with their own addictions.

Our father, also a journalist, escaped the clutches of alcoholism but possessed the same manic energy that drove so many members of his immediate family to drink. His premature death in a fiery one-person car crash left a void that we all tried to fill differently.

My sister had experienced enough drama, and exited the family tableau. And an implacable distrust settled between my older half-siblings and my mother, an overwhelmed young widow with two little girls. I became a chronic worrier and compulsive overachiever. The collapse of my family as I knew it left a hole that, in my adolescence, I looked to drugs and alcohol to fill.

For years, the losses felt too overwhelming to explore even in therapy. But in recovery, I started to come to terms with them. At the same time, I was becoming more open and less critical. Veterans of the recovery program I attended told me that I wasn’t allowed to stay angry with my sister for the choice she made, that resentments were fatal for people like us.

Psychologists call sibling estrangement an ambiguous loss. Unlike death, where the parting is final, the left-behind sister or brother mourns without ever finding resolution. This is how it felt for me — a pain that dulled with time but never quite healed.

Though one in four Americans experiences estrangement, there is scant research on the rifts between siblings. The impact can be deep and long-lasting, according to Fern Schumer Chapman, the author of several books on the subject.

“This is someone you thought should be a part of your life experience who has chosen to reject you,” said Ms. Schumer Chapman, who was estranged from her brother for 40 years. “And they’re still walking the earth.”

“How often did you think of me?” Ms. Schumer Chapman said she asked her brother, after they reconciled. “He said, ‘Every day.’ And I was really unprepared for that.”

Recently, a large longitudinal study in Germany found that estrangement can have “potentially far-reaching consequences for family functioning and individuals’ well-being.” The same study found that sibling estrangement was not uncommon, “but often merely temporary.”

And so it appeared that it could be for my sister and me — a 32-year blip.

For all the distance caused by alcoholism in our family, there was also a pattern of change. One aunt got sober, then two cousins, then my younger sister and a second cousin, then me.

So in May, I shared my baby news with my older sister through a Facebook message, the first communication we had exchanged in years.

“I wanted to let you know that you have a new niece!” I wrote, sending a stream of pictures.

She wrote back quickly, suggesting a visit.

I was receptive, but as the reunion approached, my insides churned. I feared I was setting myself up for fresh disappointment.

My father’s early death and mother’s resulting marital status — single, widowed — felt like a brand in the halls of my small-town Illinois parochial school. I often fantasized about the return of my big sister as the panacea for my isolation and loneliness.

But as the years passed and I lived through the pangs of adolescence and early adulthood without her, I let go of such a possibility. I learned to steel myself against the wave of sadness that would still sometimes come over me.

I wore that steeliness like armor as I pushed a baby stroller into the Chicago Diner in July. There my sister sat in a booth with her son — a 23-year-old nephew I was meeting for the first time. The conversation, mainly about his first impressions of Chicago, was stilted at first. Then my sister noticed my thumbs. Just like hers.

After lunch, we strolled a few blocks to the brownstone where my younger sister and I spent our early childhood. The sight of the building always conjured memories of my older sister getting down on the hardwood floor with me to play with Fisher-Price toys, and calling me “Stinky,” a nickname that as a toddler I found hilarious. Those memories shot back as I stood with my 3-month-old daughter, my long-vanished sister and her son on the sidewalk.

After our summer reunion, our relationship continued to grow. We had another visit in the fall, and several long phone calls.

“I unwittingly did a lot of things they did,” my sister said recently of our family, when I worked up the courage to ask her why she had left. “I didn’t know how to work out a conflict,” she added. “I guess I thought you just disappear.”

I struggled with how to let go of a sense of abandonment that had so indelibly shaped me. It helped that my identity had changed — I was now a woman writing her own story, and a mother, caring for a tiny baby. My siblings and I were all a bit broken; maybe gathering around my daughter would make us more whole.

Source link